Setting foot on the ancient alley

It’s taken over a month for two of the three letters I sent home to my boyfriend in Portland to arrive at our house. It’s great to see these letters again, just in time to help me write this blog.

One of the odd surprises for me about traveling in China is that pretty much nobody at the hotels we stayed at in Jiangmen or Shaoguan expected tourists to want to mail anything. The hotels had the stationery folder with the letter paper and envelopes in your room, but there were no mailboxes, nobody who worked there could sell you a postage stamp and nobody knew where the nearest post office was nor seemed interested in finding out. Once I finally did manage to get my hands on some postage stamps (our tour group bought all dozen of the postage stamps that were available for sale from the cashier at the gift shop at the Kaiping Diaolou World Heritage site) I was able to convince a hotel employee in Kaiping to mail one of my stamped letters. My other letters I mailed from a mailbox at the World Heritage site and from Wuyi University in Jiangmen.

The best understanding I could get of this is that people just don’t mail anything from hotels anymore— i’m guessing because most travelers just use the internet. Would it sound paranoid to try to read anything more into it? I did peer into a lot of storefronts around the towns and sites we visited that had post office signage but weren’t open and didn’t seem to be post offices anymore.

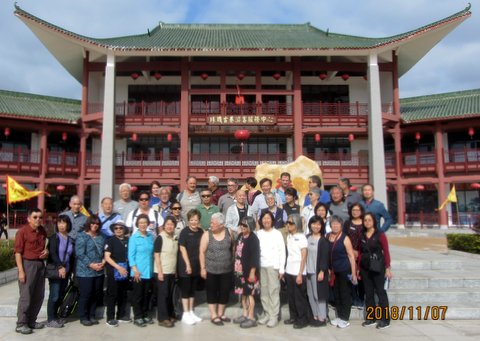

Panorama of the visitor center at Zhujixiang. Photo by Ron Chan, indeed a distant relative of mine.

One of these empty non-post-office spots was at one end of this huge, grand, much-photographed and largely vacant visitor center at the “heritage village” of Zhujixiang. (That’s it in the first photo of the slideshow. The slideshow has captions but they won’t show up on a phone.)

Our tour guide explained to us that Zhujixiang (in Chinese, 珠玑古巷, Zhuji Guxiang, “gu” meaning ancient, “xiang” meaning alley) was a village founded by Han Chinese (the dominant ethnic group of China, to which i belong) over 500 years ago as our various family groups left the central provinces of China on their way into the Guangdong region. It was a convenient first stop for travelers on the south side of Meiguan 梅关, an ancient pass through the mountains separating current Guangdong Province (where my family lived before emigrating) from Jiangxi Province.

We arrived after a long morning bus trip from Jiangmen, through the outskirts of Guangzhou and mountainous terrain covered with replanted eucalyptus forest. The town (Zhujizhen 珠玑镇) outside the heritage village was a mix of weathered 20th-century concrete and vacant, newly developed luxury condo or vacation apartment buildings, anticipating some future demand.

We ate what i think was the only mediocre lunch of the trip in a roadside restaurant whose main qualities were raising and slaughtering their own chickens and being big enough to swiftly accommodate 35+ lunch guests from a tour bus. You would think the chicken would have been great but they were pretty scrawny, tough and bony birds.

Zhujixiang strikes me as a place a foreigner would be unlikely to visit unless you’re a person of Chinese descent on a particular kind of heritage quest. It didn’t show up on any of the google searches i did before i took this trip. It was definitely the kind of place where one’s understanding of lines between history, myth, the ancient world and personal biography starts to blur. You are to believe that you are walking the exact path (via a re-paved replica) that members of your family and one hundred and eighty-two other clans followed, through the same village they maintained, over the same stone bridge, beneath the same thousand-year old banyan tree. The keepers of the heritage village welcomed us by detonating a shockingly loud bundle of firecrackers the size of a pillow to clear the alley of evil spirits, or at least deafen them. I begin to realize i’d been hearing similar explosions in the distance since we arrived in the parking lot, smelling the acrid smoke and seeing red confetti shreds blown from the heaps swept neatly to the roadside— i just didn’t know what it was yet.

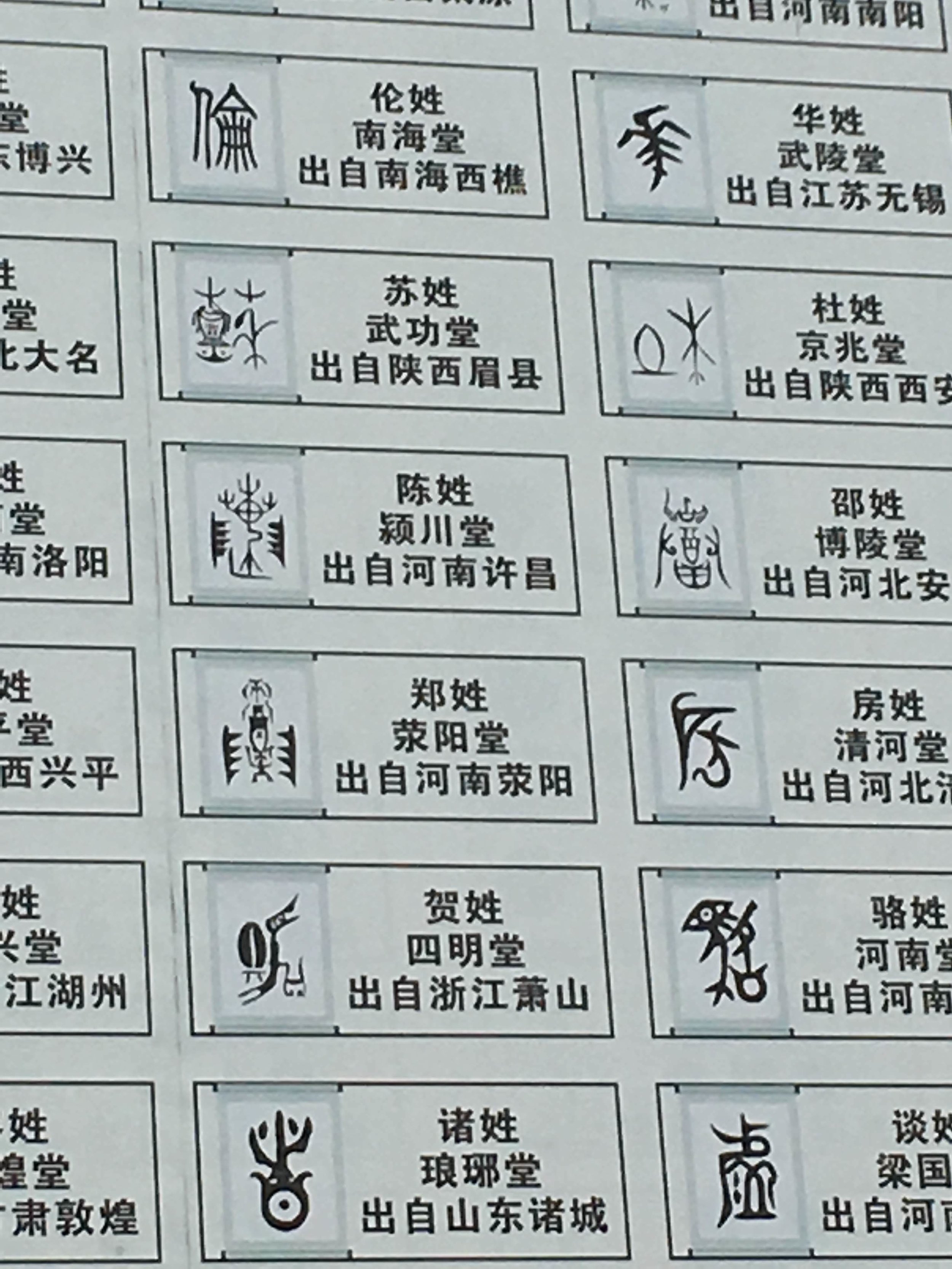

The ancient alley took us through a landscaped modern art park, filled with banners and signage touting the 183 clan surnames. We passed through a splendid gate, down the middle of a long lane of conjoined single-story, single-room primitive rammed-earth or concrete village-type houses. Each one prominently featured a sign bearing a surname of one of the 183 original clans, and contained something (a shrine, gift shop, workshop, snack vendor) or nothing. They looked convincingly old, run-down, even. The shrines consisted of a central statue representing an ancestor or important local divinity in the middle of a table with incense, fruit, tea and similar offerings neatly arranged. The merchants were unpretentious country folk proffering handmade-looking trinkets, toys, charms and keychains. Also for sale: traditional style preserved meat items (pork, duck, goose) and fistfuls of long hand-rolled cigarettes made on the spot from freshly-shredded tobacco. On site but not apparently for sale were occasional vegetables, dry grains and beans, some random chickens.

My dad and mom are the people in hats and sunglasses in the picture below. Click through the photo series to see what they’re looking at. If you want to read the photo captions, you’ll have to view this site from a tablet or computer instead of a phone.

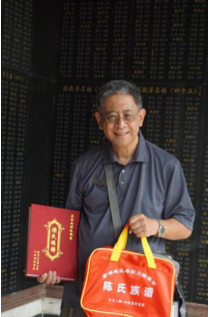

Just beyond the lanes of old village houses, each on its own kind of cul-de-sac, were twenty or so ancestral halls— each a vast, ornate, stone plaza, about the size of a whole city block, surrounded by low walls. I don’t know what any of the ones besides the Chan one looked like, but ours combined a super deluxe three-chambered ancestral shrine, repository (and vendor) of Chan genealogical documents, art museum and scenic lookout, with an extensive list of donors whose names were carved into dozens of refrigerator-sized marble plaques lining the interior walls of the structure.

From Zhujixiang we rode the tour bus to the aforementioned Meiguan (Plum Pass). I’m not sure how the plan to do all this in one day came about, but we very nearly ran out of daylight hiking up and back down the steep old road (paved in the same difficult stony style as described before.) I thought it was a pretty amazing place, though. If i could go there again, i’d want to start earlier— both for safety sake (those of us who brought flashlights were glad we did) and because there were sweet looking little view decks along the way and at the top that would have been selling snacks and tea if we had been there when they were still open. (I’d also want to go when the plum trees for which the pass is named are in bloom, which is mid January to mid February, but i’m not sure if that’ll ever happen.)

By the time our tour bus pulled into the parking lot of the (surprisingly outstanding) Holiday Inn in the (surprisingly charming) city of Shaoguan, I was definitely ready for a beer, a shower and dinner. For some reason, they had all 35+ of us eat dinner first, with our luggage and a few shopping bags of heavy 族谱 genealogy books and odd souvenirs, in the (surprisingly fancy and excellent) Chinese restaurant at the hotel. This hotel also had the best wi-fi (or maybe the least amount of other people using the wi-fi) out of the three hotels we stayed at on the trip. I was surprised to enjoy our night’s stay in a city I had never heard of before*.

* If you have a general interest in social media misinformation, violent mob mentality, and China’s labor and race issues, you might be shocked, as I was, to read about the blandly euphemistically termed “Shaoguan incident” of 2009, especially if, like me, you had total ignorance of it.